Why don't we like arguments from authority?

Contents

A tension between bayesiansim and intuition

When considering arguments from authority, there would appear to be a tension between widely shared intuitions about these arguments, and how Bayesianism treats them. Under the Bayesian definition of evidence, the opinion of experts, of people with good track records, even of individuals with a high IQ, is just another source of data. Provided the evidence is equally strong, there is nothing to distinguish it from other forms of inference such as carefully gathering data, conducting experiments, and checking proofs.

Yet we feel that there would be something wrong about someone who entirely gave up on learning and thinking, in favour the far more efficient method unquestionably adopting all expert views. Personally, I still feel embarrassed when, in conversation, I am forced to say “I believe X because Very Smart Person Y said it”.

And it’s not just that we think it unvirtuous. We strongly associate arguments from authority with irrationality. Scholastic philosophy went down a blind alley by worshipping the authority of Aristotle. We think there is something espistemicaly superior about thinking for yourself, enough to justify the effort, at least sometimes.1

Attempting to reconcile the tension

Argument screens of authority

Eliezer Yudkowsky has an excellent post, “Argument screens off authority”, about this issue. You should read it to understand the rest of my post, which will be an extension of it.

I’ll give you the beginning of the post:

Scenario 1: Barry is a famous geologist. Charles is a fourteen-year-old juvenile delinquent with a long arrest record and occasional psychotic episodes. Barry flatly asserts to Arthur some counterintuitive statement about rocks, and Arthur judges it 90% probable. Then Charles makes an equally counterintuitive flat assertion about rocks, and Arthur judges it 10% probable. Clearly, Arthur is taking the speaker’s authority into account in deciding whether to believe the speaker’s assertions.

Scenario 2: David makes a counterintuitive statement about physics and gives Arthur a detailed explanation of the arguments, including references. Ernie makes an equally counterintuitive statement, but gives an unconvincing argument involving several leaps of faith. Both David and Ernie assert that this is the best explanation they can possibly give (to anyone, not just Arthur). Arthur assigns 90% probability to David’s statement after hearing his explanation, but assigns a 10% probability to Ernie’s statement. Read more

I think Yudkowsky’s post gets things conceptually right, but ignores the important pragmatic benefits of arguments from authority. At the end of the post, he writes:

In practice you can never completely eliminate reliance on authority. Good authorities are more likely to know about any counterevidence that exists and should be taken into account; a lesser authority is less likely to know this, which makes their arguments less reliable. This is not a factor you can eliminate merely by hearing the evidence they did take into account.

It’s also very hard to reduce arguments to pure math; and otherwise, judging the strength of an inferential step may rely on intuitions you can’t duplicate without the same thirty years of experience.

And elsewhere:

Just as you can’t always experiment today, you can’t always check the calculations today. Sometimes you don’t know enough background material, sometimes there’s private information, sometimes there just isn’t time. There’s a sadly large number of times when it’s worthwhile to judge the speaker’s rationality. You should always do it with a hollow feeling in your heart, though, a sense that something’s missing.

These two quotes, I think, overstate how often checking for yourself2 is a worthwhile option, and correspondingly underjustify the claim that you should have a “hollow feeling in your heart” when you rely on authority.

Ain’t nobody got time for arguments

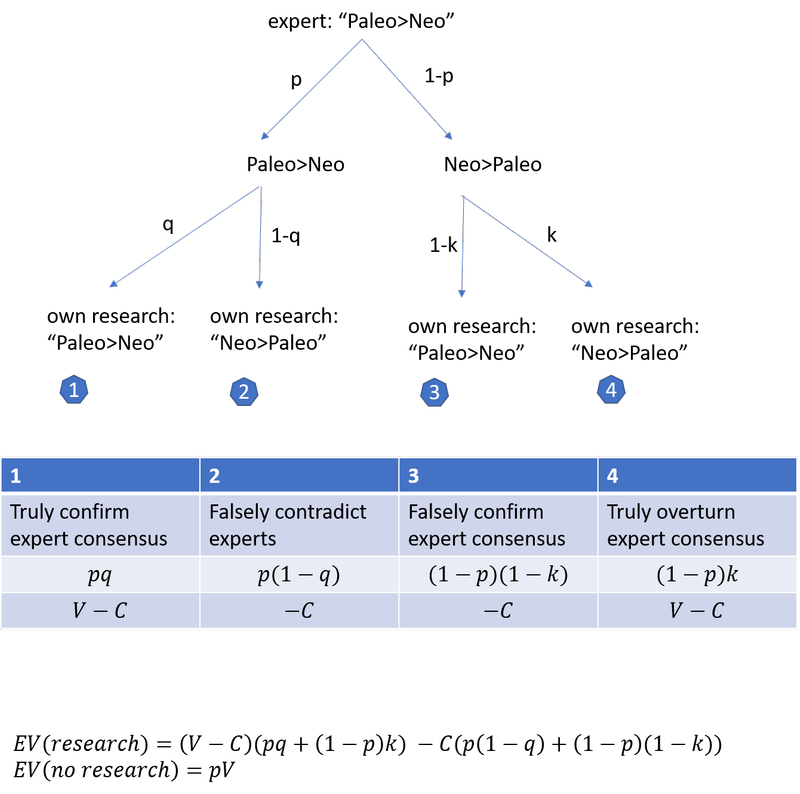

Suppose you were trying to decide which diet is best for your long-term health. The majority of experts believe that the Paleo diet is better than the Neo diet. To simplify, we can assume that either Paleo provides units more utility than Neo, or vice versa. The cost of research is . If you conduct research, you act according to your conclusions, otherwise, you do what the experts recommend. We can calculate the expected value of research using this value of information diagram:

simplifies to .

If we suppose that

- the probability that the experts are correct is

- conditional on the experts being correct, your probability of getting the right answer is

- conditional on the experts being incorrect, your probability of correctly overturning the expert view is

How long would it take to do this research? For a 50% chance of overturning the consensus, conditional on it being wrong, a realistic estimate might be several years to get a PhD-level knowledge in the field. But let’s go with one month, as a lower bound. We can conservatively estimate that to be worth $ 5000. Then you should do the research if and only if . That number is high. This suggests it would likely be instrumentally rational to just believe the experts.

Of course, this is just one toy example with very questionable numbers. (In a nascent field, such as wild animal suffering research, the “experts” may be people who know little more than you. Then could be low and could be higher.) I invite you to try your own parameter estimates.

There are also a number of complications not captured in this model:

- If the relevant belief is located in a dense part of your belief-network, where it is connected to many other beliefs, adopting the views of experts on individual questions might leave you with inconsistent beliefs. But this problem can be avoided by choosing belief-nodes that are relatively isolated, and by adopting entire world-views of experts, composed of many linked beliefs.

- In reality, you don’t just have a point probability for the parameters , , , but a probability distribution. That distribution may be very non-robust or, in other words, “flat”. Doing a little bit of research could help you learn more about whether experts are likely to be correct, tightening the distribution.

Still, I would claim that the model is not sufficiently wrong to reverse my main conclusion.

At least given numbers I find intuitive, this model suggests it’s almost never worth thinking independently instead of acting on the views of the best authorities. Perhaps thinking critically should leave me with a hollow feeling in my heart, the feeling of goals ill-pursed? Argument may screen off authority, but in the real world, ain’t nobody got time for arguments. More work needs to be done if we want to salvage our anti-authority intuitions in a Bayesian framework.

Free-riding on authority?

Here’s one attempt to do so. From a selfish individual’s point of view, V is small. But not so for a group.

Assuming that others can see when you pay the cost to acquire evidence, they come to see you as an authority, to some degree. Every member of the group thus updates their beliefs slightly based on your research, in expectation moving towards the truth.

More importantly, the value of the four outcomes from the diagram above can differ drastically under this model. In particular, the value of correctly overturning the expert consensus can be tremendous. If you publish your reasoning, the experts who can understand it may update strongly towards the truth, leading the non-experts to update as well.

It is only if we consider the positive externalities of knowledge that eschewing authority becomes rational. For selfish individuals, it is rational to free-ride on expert opinion. This suggests that our aversion to arguments from authority can partially be explained as the epistemic analogue of our dislike for free-riders.

This analysis also suggests that most learning and thinking is not done to personally acquire more accurate beliefs. It may be out of altruism, for fun, to signal intelligence, or to receive status in a community that rewards discoveries, like academia.

Is the free-riding account of our anti-authority intuitions accurate? In a previous version of this essay, I used to think so. But David Moss commented:

Even in a situation where an individual is the only non-expert, say there are only five other people and they are all experts, I think the intuition against deferring to epistemic authority would remain strong. Indeed I expect it may be even stronger than it usually is. Conversely, in a situation where there are many billions of non-experts all deferring to only a couple of experts, I expect the intuition against deferring would remain, though likely be weaker. This seems to count against the intuition being significantly driven by positive epistemic externalities.

This was a great point, and convinced me that at the very least, the free-riding picture can’t fully explain our anti-authority intuitions. However, my intuitions about more complicated cases like David’s are quite unstable; and at this point my intuitions are heavily influenced by bayesian theory as well. So it would be interesting to get more thoughtful people’s intuitions about such cases.

What to do?

It looks like the common-sense intuitions against authority are hard to salvage. Yet this empirical conclusion does not imply that, normatively, we should entirely give up on learning and thinking.

Instead the cost-benefit analysis above offers a number of slightly different normative insights:

- The majority of the value of research is altruistic value, and is realised through changing the minds of others. This may lead you to: (i) choose questions that are action-guiding for many people, even if they are not for you (ii) present your conclusions in a particularly accessible format.

- Specialisation is beneficial. It is an efficient division of labour if each person acquires knowledge in one field, and everyone accepts the authority of the specialists over their magisterium.

- Reducing C can have large benefits for an epistemic community by allowing far more people to cheaply verify arguments. This could be one reason formalisation is so useful, and has tended to propel formal disciplines towards fast progress. To an idealised solitary scientist, translating into formal language arguments he already knows with high confidence to be sound may seem like a waste of time. But the benefit of doing so is that it replaces intuitions others can’t duplicate without thirty years of experience with inferential steps that they can check mechanically with a “dumb” algorithm.

A few months after I wrote the first version of this piece, Grew Lewis wrote (my emphasis):

Modesty could be parasitic on a community level. If one is modest, one need never trouble oneself with any ‘object level’ considerations at all, and simply cultivate the appropriate weighting of consensuses to defer to. If everyone free-rode like that, no one would discover any new evidence, have any new ideas, and so collectively stagnate. Progress only happens if people get their hands dirty on the object-level matters of the world, try to build models, and make some guesses - sometimes the experts have gotten it wrong, and one won’t ever find that out by deferring to them based on the fact they usually get it right.

The distinction between ‘credence by my lights’ versus ‘credence all things considered’ allows the best of both worlds. One can say ‘by my lights, P’s credence is X’ yet at the same time ‘all things considered though, I take P’s credence to be Y’. One can form one’s own model of P, think the experts are wrong about P, and marshall evidence and arguments for why you are right and they are wrong; yet soberly realise that the chances are you are more likely mistaken; yet also think this effort is nonetheless valuable because even if one is most likely heading down a dead-end, the corporate efforts of people like you promises a good chance of someone finding a better path.

I probably agree with Greg here; and I believe that the bolded part was a crucial and somewhat overlooked part of his widely-discussed essay. While Greg believes we should form our credences entirely based on authority, he also believes it can be valuable to deeply explore object-level questions. The much more difficult question is how to navigate this trade-off, that is, how to decide when it’s worth investigating an issue.

-

This is importantly different from another concern about updating based on other people’s beliefs, that of double counting evidence or evidential overlap. Amanda Askell writes: “suppose that as I’m walking down the street I meet six people in a row who all tell me that a building four blocks away is on fire. I reasonably assume that some of these six people have seen the fire themselves or that they’ve heard that there’s a fire from different people who have seen it. I conclude that I’ve got good testimonial evidence that there’s a fire four blocks away. But suppose that none of them have seen the fire: they’ve all just left a meeting in which a charismatic person Bob told them that there is a fire four blocks away. If I knew that there wasn’t actually any more evidence for the fire claim than Bob’s testimony, I would not have been so confident that there’s a fire four blocks away.

In this case, the credence that I ended up with was based on the testimony of those six people, which I reasonably assumed represented a diverse body of evidence. This means that anyone asking me what makes me confident that there’s a fire will also receive misleading evidence that there’s a diverse body of evidence for the fire claim. This is a problem of evidential overlap: when several people independently tell me that they have some credence in P, I have a reasonable prior about how much overlap there is in their evidence. But in cases like the one above, that prior is incorrect.”

The problem of evidential overlap stems from reasonable-seeming but incorrect priors about the truth of a proposition, conditional on (the conjunction of) various testimonies. The situations I want to talk about concern agents with entirely correct priors, who update on testimony the adequate Bayesian amount. In my case the ideal Bayesian behaves counterintuitively, in Amanda’s example, Bayesianism and intuition agree since bad priors lead to bad beliefs. ↩

-

In this post, I use “checking for yourself”, “thinking for yourself”, “thinking and learning”, etc., as a stand-in for anything that helps evaluate the truth-value of the “good argument” node in Yudkowsky’s diagram. This could include gathering empirical evidence, checking arguments and proofs, as well as acquiring the skills necessary to do this. ↩