The special case of the normal likelihood function

Summary1: The likelihood function implied by an estimate with standard deviation is the probability density function (PDF) of a . Though this might sound intuitive, it’s actually a special case. If we don’t firmly grasp that it’s an exception, it can be confusing.

Suppose that a study has the point estimator for the parameter . The study results are an estimate (typically a regression coefficient), and an estimated standard deviation2 .

In order to know how to combine this information with a prior over in order to update our beliefs, we need to know what is the likelihood function implied by the study. The likelihood function is the probability of observing the study data given different values for . It is formed from the probability of the observation that conditional on , but viewed and used as a function of only3:

The event “” is often shortened to just “” when the meaning is clear from context, so that the function can be more briefly written .

So, what is ? In a typical regression context, is assumed to be approximately normally distributed around , due to the central limit theorem. More precisely, , and equivalently .

is seldom known, and is often replaced with its estimate , allowing us to write , where only the parameter is unknown4.

We can plug this into the definition of the likelihood function:

We could just leave it at that. is the function5 above, and that’s all we need to compute the posterior. But a slightly different expression for is possible. After factoring out the square,

we make use of the fact that to rewrite with the positions of and flipped:

We then notice that is none other than

So, for all and for all , .

The key thing to realise is that this is a special case due to the fact that the functional form of the normal PDF is invariant to substituting and for each other. For many other distributions of , we cannot apply this procedure.

This special case is worth commenting upon because it has personally lead me astray in the past. I often encountered the case where is normally distributed, and I used the equality above without deriving it and understanding where it comes from. It just had a vaguely intuitive ring to it. I would occasionally slip into thinking it was a more general rule, which always resulted in painful confusion.

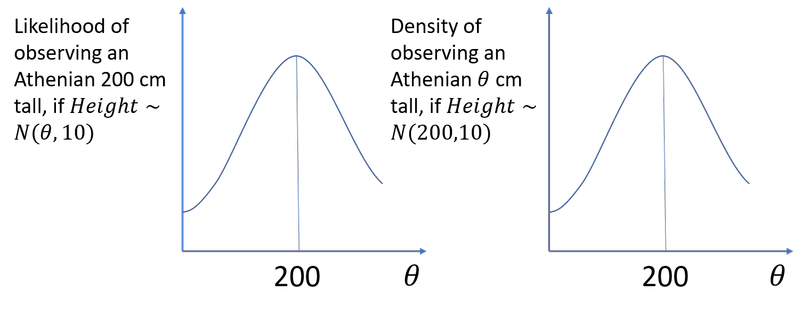

To understand the result, let us first illustrate it with a simple numerical example. Suppose we observe an Athenian man cm tall. For all , the likelihood of this observation if Athenian men’s heights followed an is the same number as the density of observing an Athenian cm tall if Athenian men’s heights followed a 6.

Graphical representation of

When encountering this equivalence, you might, like me, sort of nod along. But puzzlement would be a more appropriate reaction. To compute the likelihood of our 200 cm Athenian under different -values, we can substitute a totally different question: “assuming that , what is the probability of seeing Athenian men of different sizes?”.

The puzzle is, I think, best resolved by viewing it as a special case, an algebraic curiosity that only applies to some distributions. Don’t even try to build an intuition for it, because it does not generalise.

To help understand this better, let’s look at at a case where the procedure cannot be applied.

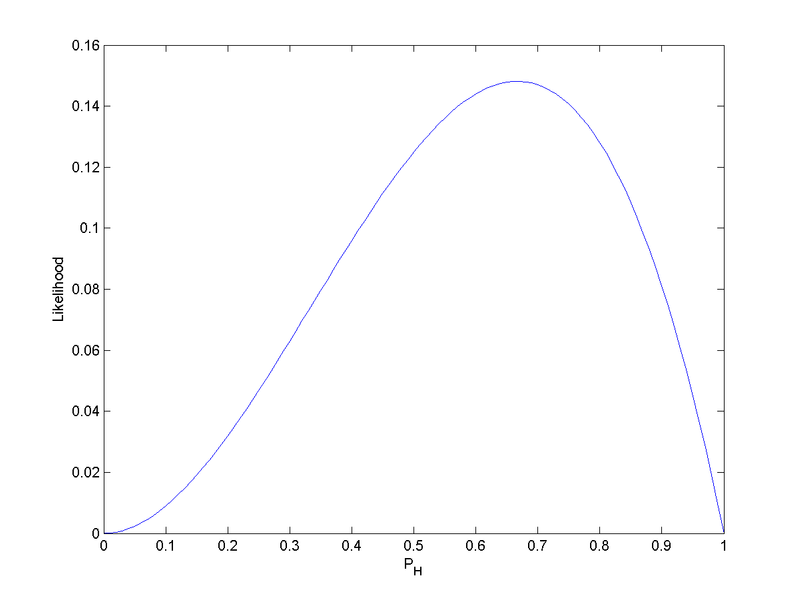

Suppose for example that is binomially distributed, representing the number of successes among independent trials with success probability . We’ll write .

’s probability mass function is

Meanwhile, the likelihood function for the observation of successes is

To attempt to take the PMF , set its parameter equal to , and obtain the likelihood function would not just give incorrect values, it would be a domain error. Regardless of how we set its parameters, could never be equal to the likelihood function , because is defined on , whereas is defined on .

The likelihood function for the binomial probability of a biased coin landing heads-up, given that we have observed . It is defined on . (The constant factor is omitted, a common practice with likelihood functions, because these constant factors have no meaning and make no difference to the posterior distribution.)

It’s hopefully now quite intuitive that the case where is normally distributed was a special case.7

Let’s recapitulate.

The likelihood function is the probability of viewed as a function of only. It is absolutely not a density of .

In the special case where is normally distributed, we have the confusing ability of being able to express this function as if it were the density of under a distribution that depends on .

I think it’s best to think of that ability as an algebraic coincidence, due to the functional form of the normal PDF. We should think of in the case where is normally distributed as just another likelihood function.

Finally, I’d love to know if there is some way to view this special case as enlightening rather than just a confusing exception.

I believe that to say that a (where denotes the PDF of a distribution with one parameter that we wish to single out and a vector of other parameters), is equivalent to saying that the PDF is symmetric around its singled-out parameter. For example, a is symmetric around its parameter . But this hasn’t seemed insightful to me. Please write to me if you know an answer to this.

-

Thanks to Gavin Leech and Ben West for feedback on a previous versions of this post. ↩

-

I do not use the confusing term ‘standard error’, which I believe should mean but is often also used to also denote its estimate . ↩

-

I use uppercase letters and to denote random variables, and lower case and for particular values (realizations) these random variables could take. ↩

-

A more sophisticated approach would be to let be another unknown parameter over which we form a prior; we would then update our beliefs jointly about and . See for example Bolstad & Curran (2016), Chapter 17, “Bayesian Inference for Normal with Unknown Mean and Variance”. ↩

-

I don’t like the term “likelihood distribution”, I prefer “likelihood function”. In formal parlance, mathematical distributions are a generalization of functions, so it’s arguably technically correct to call any likelihood function a likelihood distribution. But in many contexts, “distribution” is merely used as short for “probability distribution”. So “likelihood distribution” runs the risk of making us think of “likelihood probability distribution” – but the likelihood function is not generally a probability distribution. ↩

-

We are here ignoring any inadequacies of the assumption, including but not limited to the fact that one cannot observe men with negative heights. ↩

-

Another simple reminder that the procedure couldn’t possibly work in general is that in general the likelihood function is not even a PDF at all. For example, a broken thermometer that always gives the temperature as 20 degrees has for all , which evidently does not integrate to 1 over all values of .

To take a different tack, the fact that the likelihood function is invariant to reparametrization also illustrates that it is not a probability density of (thanks to Gavin Leech for the link). ↩