Philosophy success story V: Bayesianism

This is part of my series on success stories in philosophy. See this page for an explanation of the project and links to other items in the series.

Contents

- Bayesianism: the correct theory of rational inference

- Science as a special case of rational inference

- Previous theories of science

- The Quine-Duhem problem

- Uncertain judgements and value of information (resilience)

- Issues around Occam’s razor

Bayesianism: the correct theory of rational inference

Unless specified otherwise, by “Bayesianism” I mean normative claims constraining rational credences (degrees of belief), not any descriptive claim. Bayesianism so understood has, I claim, consensus support among philosophers. It has two core claims: probabilism and conditionalisation.

Probabilism

What is probabilism? (Teruji Thomas, Degrees of Belief, Part I: degrees of belief and their structure.)

Suppose that Clara has some confidence that is true. Then, in so far as Clara is rational:

- We can quantify credences: we can represent Clara’s credence in by a number, . The higher the number, the more confident Clara is that is true.

- More precisely, we can choose these numbers to fit together in a certain way: they satisfy the probability axioms, that is, they behave like probabilities do: (a) is always between 0 and 1. (b) (c) .

Conditionalisation

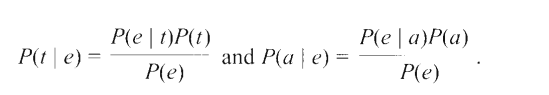

Suppose you gain evidence E. Let Cr be your credences just before and Cr_NEW new your credences just afterwards. Then, insofar as you are rational, for any proposition P: .1

Justifications for probabilism and conditionalisation

Dutch book arguments

The basic idea: an agent failing to use probabilism or conditionalisation can be made to accept a series of bets that will lead to a sure loss (such a series of bets is called a dutch book).

I won’t go into detail here, as this has been explained very well in many places. See for instance, Teruji Thomas, Degrees of Belief II or Earman, Bayes or Bust Chapter 2.

Cox’s theorem

Bayes or Bust, Chapter 2, p 45:

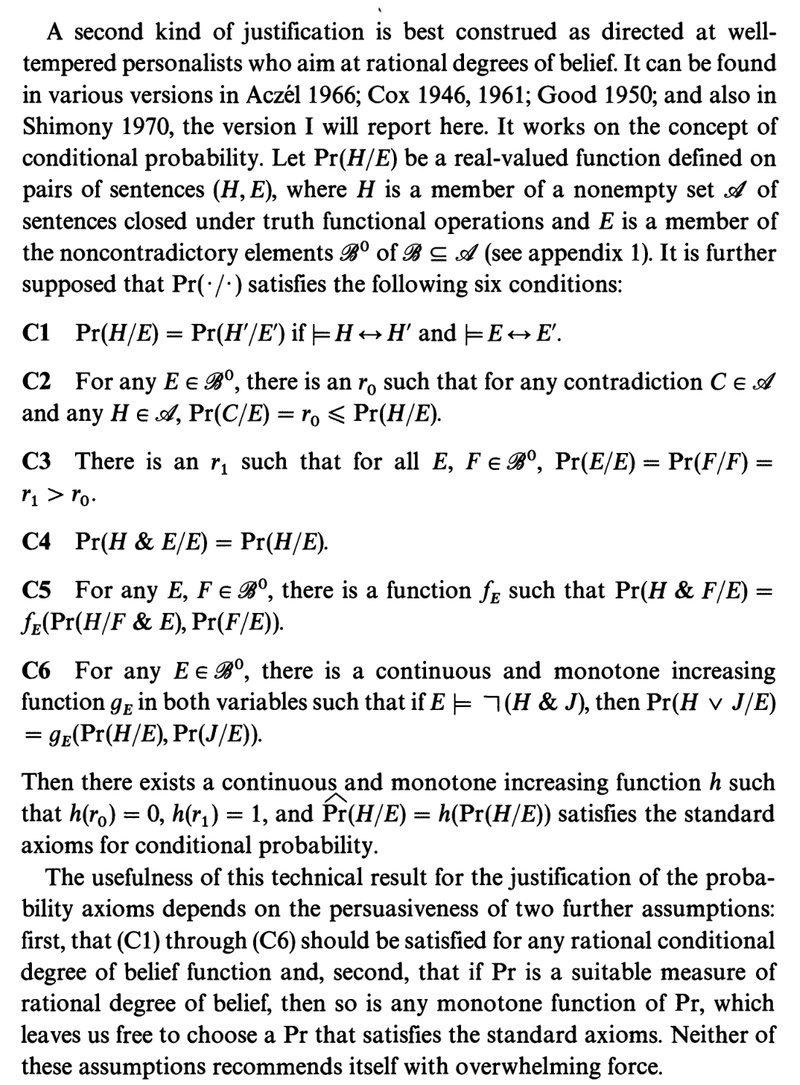

Jaynes (2011, 1.7 p.17) thinks the axioms formalise “qualitative correspondence with common sense” — but his argument is sketchy and I rather agree with Earman that the assumptions of Cox’s theorem do not recommend themselves with overwhelming force.

Obviousness argument

Dutch books and Cox’s theorem aside, there’s something to be said for the sheer intuitive plausibility of probabilism and conditionalisation. If you want to express your beliefs as a number between 0 and 1, it just seems obvious that they should behave like probabilities. To me, accepting probabilism and conditionalisation outright feels more compelling than the premises of Cox’s theorem do. “Degrees of belief should behave like probabilities” seems near-tautological.

Science as a special case of rational inference

Philosophers have long realised that science was extremely successful: predicting the motions of the heavenly bodies, building aeroplanes, producing vaccines, and so on. There must be a core principle underlying the disparate activities of scientists — measuring, experimenting, writing equations, going to conferences, etc. So they set about trying to find this core principle, in order to explain the success of science (the descriptive project) and to apply the core principle more accurately and more generally (normative project). This was philosophy of science.

Scientists are presitigious people in universities. Science, lab coats and all, seems like a specific activity separate from normal life. So it seemed natural that there should be a philosophy of science. This turned out to be a blind alley. The solution to philosophy of science was to come from a far more general theory — the theory of rational inference. This would reveal science as merely a watered-down special case of rational inference.

We will now see how Bayesianism solves most of the problems philosophers of science were preoccupied with. As far as I can tell, this view has wide acceptance among philosophers.

Now let’s review how people were confused and how Bayesianism dissolved the confusion.

Previous theories of science

Hypothetico-deductivism

SEP:

In a seminal essay on induction, Jean Nicod (1924) offered the following important remark:

Consider the formula or the law: F entails G. How can a particular proposition, or more briefly, a fact affect its probability? If this fact consists of the presence of G in a case of F, it is favourable to the law […]; on the contrary, if it consists of the absence of G in a case of F, it is unfavourable to this law. (219, notation slightly adapted)

SEP:

The central idea of hypothetico-deductive (HD) confirmation can be roughly described as “deduction-in-reverse”: evidence is said to confirm a hypothesis in case the latter, while not entailed by the former, is able to entail it, with the help of suitable auxiliary hypotheses and assumptions. The basic version (sometimes labelled “naïve”) of the HD notion of confirmation can be spelled out thus:

For any such that is consistent:

HD-confirms relative to if and only if and ;

HD-disconfirms relative to if and only if , and ;

is HD-neutral for hypothesis relative to otherwise.

Hypothetico-deductivism and the problem of irrelevant conjunction

SEP:

The irrelevant conjunction paradox. Suppose that confirms relative to (possibly empty) . Let statement e logically consistent with , but otherwise ntirely irrelevant for all of those conjuncts. Does confirm (relative to ) as it does with ? One would want to say no, and this implication can be suitably reconstructed in Hempel’s theory. HD-confirmation, on the contrary, can not draw yhis distinction: it is easy to show that, on the conditions specified, if the HD clause for confirmation is satisfied for and (given ), so it is for and (given ). (This is simply because, if , then , too, by the monotonicity of classical logical entailment.)

The Bayesian solution:

In the statement below, indicating this result, the irrelevance of for hypothesis and evidence (relative to ) is meant to amount to the probabilistic independence of from and their conjunction (given ), that is, to , and , respectively.

Confirmation upon irrelevant conjunction (ordinal solution) (CIC)

For any and any if confirms relative to and is irrelevant for and relative to , then</p>So, even in case it is qualitatively preserved across the tacking of onto , the positive confirmation afforded by is at least bound to quantitatively decrease thereby.

Instance confirmation

Bayes or Bust (p. 63):

When Carl Hempel published his seminal “Studies in the Logic of Confir- mation” (1945), he saw his essay as a contribution to the logical empiricists’ program of creating an inductive logic that would parallel and comple- ment deductive logic. The program, he thought, was best carried out in three stages: the first stage would provide an explication of the qualitative concept of confirmation (as in ‘E confirms H’); the second stage would tackle the comparative concept (as in ‘E confirms H more than E’ confirms H”); and the final stage would concern the quantitative concept (as in ‘E confirms H to degree r’). In hindsight it seems clear (at least to Bayesians) that it is best to proceed the other way around: start with the quantitative concept and use it to analyze the comparative and qualitative notions. […]

Hempel’s basic idea for finding a definition of qualitative confirmation satisfying his adequacy conditions was that a hypothesis is confirmed by its positive instances. This seemingly simple and straightforward notion turns out to be notoriously difficult to pin down. Hempel’s own explica— tion utilized the notion of the development of a hypothesis for a finite set I of individuals. Intuitively, is what asserts about a domain consisting ofjust the individuals in . Formally, for a quantified is arrived at by peeling off universal quantifiers in favor of conjunctions over I and existential quantifiers in favor of disjunctions over I . Thus, for example, if and H is (e.g., “Everybody loves somebody”), is . We are now in a position to state the main definition[] that constitute[s] Hempel’s account:

- E directly Hempel-confirms H iff , where is the class of individuals mentioned in .

It’s easy to check that Hempel’s instance confirmation, like Bayesiansim, successfully avoids the paradox or irrelevant conjunction. But it’s famously vulnerable to the following problem case.

Instance confirmation and the paradox of the ravens

The ravens paradox (Hempel 1937, 1945). Consider the following statements:

, i.e., all ravens are black;

, i.e., is a black raven;

, i.e., is a non-black non-raven (say, a green apple).

Is hypothesis confirmed by and alike? One would want to say no, but Hempel’s theory is unable to draw this distinction. Let’s see why.

As we know, (directly) Hempel-confirms , according to Hempel’s reconstruction of Nicod. By the same token, (directly) Hempel-confirms the hypothesis that all non-black objects are non-ravens, i.e., . But ( and are just logically equivalent). So, (the observation report of a non-black non-raven), like (black raven), does (indirectly) Hempel-confirm (all ravens are black). Indeed, as entails , it can be shown that is (directly) Hempel-confirmed by the observation of any object that is not a raven (an apple, a cat, a shoe, or whatever), apparently disclosing puzzling “prospects for indoor ornithology” (Goodman 1955, 71).

Just as HD, Bayesian relevance confirmation directly implies that confirms given and confirms given (provided, as we know, that and That’s because and But of course, to have confirmed, sampling ravens and finding a black one is intuitively more significant than failing to find a raven while sampling the enormous set of the non-black objects. That is, it seems, because the latter is very likely to obtain anyway, whether or not is true, so that is actually quite close to unity. Accordingly, (SP) implies that is indeed more strongly confirmed by given than it is by given —that is, —as long as the assumption applies.

Bootstrapping and relevance relations

In a pre-Bayesian attempt to solve the problem of the ravens, people developed some complicated and ultimately unconvincing theories.

SEP:

To overcome the latter difficulty, Clark Glymour (1980a) embedded a refined version of Hempelian confirmation by instances in his analysis of scientific reasoning. In Glymour’s revision, hypothesis h is confirmed by some evidence e even if appropriate auxiliary hypotheses and assumptions must be involved for e to entail the relevant instances of h. This important theoretical move turns confirmation into a three-place relation concerning the evidence, the target hypothesis, and (a conjunction of) auxiliaries. Originally, Glymour presented his sophisticated neo-Hempelian approach in stark contrast with the competing traditional view of so-called hypothetico-deductivism (HD). Despite his explicit intentions, however, several commentators have pointed out that, partly because of the due recognition of the role of auxiliary assumptions, Glymour’s proposal and HD end up being plagued by similar difficulties (see, e.g., Horwich 1983, Woodward 1983, and Worrall 1982).

Falsificationism

“statements or systems of statements, in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting with possible, or conceivable observations” (Popper 1962, 39).

SEP:

For Popper […] the important point was not whatever confirmation successful prediction offered to the hypotheses but rather the logical asymmetry between such confirmations, which require an inductive inference, versus falsification, which can be based on a deductive inference. […]

Popper stressed that, regardless of the amount of confirming evidence, we can never be certain that a hypothesis is true without committing the fallacy of affirming the consequent. Instead, Popper introduced the notion of corroboration as a measure for how well a theory or hypothesis has survived previous testing.

Popper was clearly onto something, as in his critique of psychoanalysis:

Neither Freud nor Adler excludes any particular person’s acting in any particular way, whatever the outward circumstances. Whether a man sacrificed his life to rescue a drowning child (a case of sublimation) or whether he murdered the child by drowning him (a case of repression) could not possibly be predicted or excluded by Freud’s theory; the theory was compatible with everything that could happen.

But his stark asymmetry between logically disproving a theory and “corroborating” it was actually a mistake. And it led to many problems.

First, successful science often did not involve rejecting a theory as disproven when it failed an empirical test. SEP:

Originally, Popper thought that this meant the introduction of ad hoc hypotheses only to save a theory should not be countenanced as good scientific method. These would undermine the falsifiabililty of a theory. However, Popper later came to recognize that the introduction of modifications (immunizations, he called them) was often an important part of scientific development. Responding to surprising or apparently falsifying observations often generated important new scientific insights. Popper’s own example was the observed motion of Uranus which originally did not agree with Newtonian predictions, but the ad hoc hypothesis of an outer planet explained the disagreement and led to further falsifiable predictions.

Second, Popper’s idea of corroboration was intolerably vague. A theory is supposed to be well-corroborated if it stuck its neck out by being falsifiable, and has resisted falsification for a long time. But how, for instance, do we compare how well-corroborated two theories are? And how are we supposed to act in the meantime, when there are still several contending theories? The intuition is that well-tested theories should have higher probability, but Popper’s “corroboration” idea is ill-equipped to account for this.

Bayesianism dissolves these problems, but captures the grain of truth in falsificationism. I’ll just quote from the Arbital page on the bayesian view of scientific virtues, which is despite its silly style is excellent, and should probably be read in full.

In a Bayesian sense, we can see a hypothesis’s falsifiability as a requirement for obtaining strong likelihood ratios in favor of the hypothesis, compared to, e.g., the alternative hypothesis “I don’t know.”

Suppose you’re a very early researcher on gravitation, named Grek. Your friend Thag is holding a rock in one hand, about to let it go. You need to predict whether the rock will move downward to the ground, fly upward into the sky, or do something else. That is, you must say how your theory assigns its probabilities over and

As it happens, your friend Thag has his own theory which says “Rocks do what they want to do.” If Thag sees the rock go down, he’ll explain this by saying the rock wanted to go down. If Thag sees the rock go up, he’ll say the rock wanted to go up. Thag thinks that the Thag Theory of Gravitation is a very good one because it can explain any possible thing the rock is observed to do. This makes it superior compared to a theory that could only explain, say, the rock falling down.

As a Bayesian, however, you realize that since and are mutually exclusive and exhaustive possibilities, and something must happen when Thag lets go of the rock, the conditional probabilities must sum to

If Thag is “equally good at explaining” all three outcomes - if Thag’s theory is equally compatible with all three events and produces equally clever explanations for each of them - then we might as well call this probability for each of and . Note that Thag theory’s is isomorphic, in a probabilistic sense, to saying “I don’t know.”

But now suppose Grek make falsifiable prediction! Grek say, “Most things fall down!”

Then Grek not have all probability mass distributed equally! Grek put 95% of probability mass in Only leave 5% probability divided equally over and in case rock behave like bird.

Thag say this bad idea. If rock go up, Grek Theory of Gravitation disconfirmed by false prediction! Compared to Thag Theory that predicts 1/3 chance of will be likelihood ratio of 2.5% : 33% ~ 1 : 13 against Grek Theory! Grek embarrassed!

Grek say, she is confident rock does go down. Things like bird are rare. So Grek willing to stick out neck and face potential embarrassment. Besides, is more important to learn about if Grek Theory is true than to save face.

Thag let go of rock. Rock fall down.

This evidence with likelihood ratio of 0.95 : 0.33 ~ 3 : 1 favoring Grek Theory over Thag Theory.

“How you get such big likelihood ratio?” Thag demand. “Thag never get big likelihood ratio!”

Grek explain is possible to obtain big likelihood ratio because Grek Theory stick out neck and take probability mass away from outcomes and risking disconfirmation if that happen. This free up lots of probability mass that Grek can put in outcome to make big likelihood ratio if happen.

Grek Theory win because falsifiable and make correct prediction! If falsifiable and make wrong prediction, Grek Theory lose, but this okay because Grek Theory not Grek.

The Quine-Duhem problem

SEP:

Duhem (he himself a supporter of the HD view) pointed out that in mature sciences such as physics most hypotheses or theories of real interest can not be contradicted by any statement describing observable states of affairs. Taken in isolation, they simply do not logically imply, nor rule out, any observable fact, essentially because (unlike “all ravens are black”) they involve the mention of unobservable entities and processes. So, in effect, Duhem emphasized that, typically, scientific hypotheses or theories are logically consistent with any piece of checkable evidence. […]

Let us briefly consider a classical case, which Duhem himself thoroughly analyzed: the wave vs. particle theories of light in modern optics. Across the decades, wave theorists were able to deduce an impressive list of important empirical facts from their main hypothesis along with appropriate auxiliaries, diffraction phenomena being only one major example. But many particle theorists’ reaction was to retain their hypothesis nonetheless and to reshape other parts of the “theoretical maze” (i.e., k; the term is Popper’s, 1963, p. 330) to recover those observed facts as consequences of their own proposal.

Quine took this idea to its radical conclusion with his confirmation holism. Wikipedia:

Duhem’s idea was, roughly, that no theory of any type can be tested in isolation but only when embedded in a background of other hypotheses, e.g. hypotheses about initial conditions. Quine thought that this background involved not only such hypotheses but also our whole web-of-belief, which, among other things, includes our mathematical and logical theories and our scientific theories. This last claim is sometimes known as the Duhem–Quine thesis. A related claim made by Quine, though contested by some (see Adolf Grünbaum 1962), is that one can always protect one’s theory against refutation by attributing failure to some other part of our web-of-belief. In his own words, “Any statement can be held true come what may, if we make drastic enough adjustments elsewhere in the system.”

Bayes or Bust p 73:

It makes a nice sound when it rolls off the tongue to say that our claims about the physical world face the tribunal of experience not individually but only as a corporate body. But scientists, no less than business executives, do not typically act as if they are at a loss as to how to distribute praise through the corporate body when the tribunal says yea, or blame when the tribunal says nay. This is not to say that there is always a single correct way to make the distribution, but it is to say that in many cases there are firm intuitions.

Howson and Urbach 2006 (p 108):

We shall illustrate the argument through a historical example that Lakatos (1970, pp. 138-140; 1968, pp. l74-75) drew heavily upon. In the early nineteenth century, William Prout (1815, 1816), a medical practitioner and chemist, advanced the idea that the atomic weight of every element is a whole-number multiple of the atomic weight of hydrogen, the underlying assumption being that all matter is built up from different combinations of some basic element. Prout believed hydrogen to be that fundamental building block. Now many of the atomic weights recorded at the time were in fact more or less integral multiples of the atomic weight of hydrogen, but some deviated markedly from Prout’s expectations. Yet this did not shake the strong belief he had in his hypothesis, for in such cases he blamed the methods that had been used to measure those atomic weights. Indeed, he went so far as o adjust the atomic weight of the element chlorine, relative to that f hydrogen, from the value 35.83, obtained by experiment, to 36, he nearest whole number. […]

Prout’s hypothesis t, together with an appropriate assumption a, asserting the accuracy (within specified limits) of the measuring techniques, the purity of the chemicals employed, and so forth , implies that the ratio of the measured atomic weights of chlorine and hydrogen will approximate (to a specified degree) a whole number. In 1815 that ratio was reported as 35.83-call this the evidence e-a value judged to be incompatible with the conjunction of t and a. The posterior and prior probabilities of t and of a are related by Bayes’s theorem, as follows:

[…] Consider first the prior probabilities of and of . J.S. Stas, a distinguished Belgian chemist whose careful atomic weight measurements were highly influential, gives us reason to think that chemists of the period were firmly disposed to believe in t. […] It is less easy to ascertain how confident Prout and his contemporaries were in the methods used to measure atomic weights, but their confidence was probably not great, in view of the many clear sources of error. […] On the other hand, the chemists of the time must have felt that that their atomic weight measurements were more likely to be accurate than not, otherwise they would hardly have reported them. […] For these reasons, we conjecture that was in the neighbourhood of 0.6 and that was around 0.9, and these are the figures we shall work with. […]

We will follow Dorling in taking and to be independent, viz, and hence, . As Dorling points out (1996), this independence assumption makes the calculations simpler but is not crucial to the argument. […]

Finally, Bayes’s theorem allows us to derive the posterior probabilities in which we are interested:

(Recall that and ) We see then that the evidence provided by the measured atomic weight of chlorine affects Prout’s hypothesis and the set of auxiliary hypotheses very differently; for while the probability of the first is scarcely changed, that of the second is reduced to a point where it has lost all credibility

Uncertain judgements and value of information (resilience)

Crash course in state spaces and events: There is a set of states which represents the ways the world could be. Sometimes is described as the set of “possible worlds” (SEP). An event is a subset of . There are many states of the world where Labour wins the next election. The event “Labour wins the next election” is the set of these states.

Here is the important point: a single numerical probability for event is not just the probability you assign to one state of the world. It’s a sum over the probabilities assigned to states in . We should think of ideal Bayesians as having probability distributions over the state space, not just scalar probabilities for events.

This simple idea is enough to cut through many decades of confusion. SEP:

probability theory seems to impute much richer and more determinate attitudes than seems warranted. What should your rational degree of belief be that global mean surface temperature will have risen by more than four degrees by 2080? Perhaps it should be 0.75? Why not 0.75001? Why not 0.7497? Is that event more or less likely than getting at least one head on two tosses of a fair coin? It seems there are many events about which we can (or perhaps should) take less precise attitudes than orthodox probability requires. […] As far back as the mid-nineteenth century, we find George Boole saying:

It would be unphilosophical to affirm that the strength of that expectation, viewed as an emotion of the mind, is capable of being referred to any numerical standard. (Boole 1958 [1854]: 244)

People have long thought there is a distinction between risk (probabilities different from 0 or 1) and ambiguity (imprecise probabilities):

One classic example of this is the Ellsberg problem (Ellsberg 1961).

I have an urn that contains ninety marbles. Thirty marbles are red. The remainder are blue or yellow in some unknown proportion.

Consider the indicator gambles for various events in this scenario. Consider a choice between a bet that wins if the marble drawn is red (I), versus a bet that wins if the marble drawn is blue (II). You might prefer I to II since I involves risk while II involves ambiguity. A prospect is risky if its outcome is uncertain but its outcomes occur with known probability. A prospect is ambiguous if the outcomes occur with unknown or only partially known probabilities.

To deal with purported ambiguity, people developed models where the probability lies in some range. These probabilities were called “fuzzy” or “mushy”.

Evidence can be balanced because it is incomplete: there simply isn’t enough of it. Evidence can also be balanced if it is conflicted: different pieces of evidence favour different hypotheses. We can further ask whether evidence tells us something specific—like that the bias of a coin is 2/3 in favour of heads—or unspecific—like that the bias of a coin is between 2/3 and 1 in favour of heads.

Fuzzy probabilities gave rise to a number of problem cases, which, predictably engendered a wide literature. The SEP article notes the problems of:

- Dilation (Imprecise probabilists violate the reflection principle)

- Belief intertia (How do we learn from an imprecise prior?)

- Decision making (How should an imprecise probabilist act? Can she avoid dutch books?)

A PhilPapers search indicates that at least 65 papers have been published on these topics.

The Bayesian solution is simply: when you are less confident, you have a flatter probability distribution, though it may have the same mean. Flatter distributions move more in response to evidence. They are less resilient. See Skyrms (2011) or Leitgeb (2014). It’s not surprising that single probabilities don’t adequately describe your evidential state, since they are summary statistics over a distribution.

Issues around Occam’s razor

SEP distinguishes three questions about simplicity:

(i) How is simplicity to be defined? [Definition]

(ii) What is the role of simplicity principles in different areas of inquiry? [Usage]

(iii) Is there a rational justification for such simplicity principles? [Justification]

The Bayesian solution to (i) is to formalise Occam’s razor as a statement about which priors are better than others. Occam’s razor is not, as many philosophers have thought, a rule of inference, but a constraint on prior belief. One should have a prior that assigns higher probability to simpler worlds. SEP:

Jeffreys argued that “the simpler laws have the greater prior probability,” and went on to provide an operational measure of simplicity, according to which the prior probability of a law is , where k = order + degree + absolute values of the coefficients, when the law is expressed as a differential equation (Jeffreys 1961, p. 47).

Since then, the definition of simplicity has been further formalised using algorithmic information theory. The very informal gloss is that we formalise hypotheses as by the shortest computer program that can fully describe them, and our prior weights each hypothesis by its simplicity (, where is the program length).

This algorithmic formalisation, finally, sheds light on the limits of this understanding of simplicity, and provides an illuminating new interpretation of Goodman’s new riddle of induction. The key idea is that we can only formalise simplicity relative to a programming language (or relative to a universal turing machine).

Hutter and Rathmanner 2011, Section 5.9 “Andrey Kolmogorov”:

Natural Turing Machines. The final issue is the choice of Universal Turing machine to be used as the reference machine. The problem is that there is still subjectivity involved in this choice since what is simple on one Turing machine may not be on another. More formally, it can be shown that for any arbitrarily complex string as measured against the UTM there is another UTM machine for which has Kolmogorov complexity . This result seems to undermine the entire concept of a universal simplicity measure but it is more of a philosophical nuisance which only occurs in specifically designed pathological examples. The Turing machine would have to be absurdly biased towards the string which would require previous knowledge of . The analogy here would be to hard-code some arbitrary long complex number into the hardware of a computer system which is clearly not a natural design. To deal with this case we make the soft assumption that the reference machine is natural in the sense that no such specific biases exist. Unfortunately there is no rigorous definition of natural but it is possible to argue for a reasonable and intuitive definition in this context.

Vallinder 2012, Section 4.1 “Language dependence”:

In section 2.4 we saw that Solomonoff’s prior is invariant under both reparametrization and regrouping, up to a multiplicative constant. But there is another form of language dependence, namely the choice of a uni- versal Turing machine.

There are three principal responses to the threat of language dependence. First, one could accept it flat out, and admit that no language is better than any other. Second, one could admit that there is language dependence but argue that some languages are better than others. Third, one could deny language dependence, and try to show that there isn’t any.

For a defender of Solomonoff’s prior, I believe the second option is the most promising. If you accept language dependence flat out, why intro- duce universal Turing machines, incomputable functions, and other need- lessly complicated things? And the third option is not available: there isn’t any way of getting around the fact that Solomonoff’s prior depends on the choice of universal Turing machine. Thus, we shall somehow try to limit the blow of the language dependence that is inherent to the framework. Williamson (2010) defends the use of a particular language by saying that an agent’s language gives her some information about the world she lives in. In the present framework, a similar response could go as follows. First, we identify binary strings with propositions or sensory observations in the way outlined in the previous section. Second, we pick a UTM so that the terms that exist in a particular agent’s language gets low Kolmogorov complexity.

If the above proposal is unconvincing, the damage may be limited some- what by the following result. Let be the Kolmogorov complexity of relative to universal Turing machine , and let be the Kolmogorov complexity of relative to Turing machine (which needn’t be universal). We have that That is: the difference in Kolmogorov complexity relative to and relative to is bounded by a constant that depends only on these Turing machines, and not on . (See Li and Vitanyi (1997, p. 104) for a proof.) This is somewhat reassuring. It means that no other Turing machine can outperform infinitely often by more than a fixed constant. But we want to achieve more than that. If one picks a UTM that is biased enough to start with, strings that intuitively seem complex will get a very low Kolmogorov complexity. As we have seen, for any string it is always possible to find a UTM such that . If , the corresponding Solomonoff prior will be at least . So for any binary string, it is always possible to find a UTM such that we assign that string prior probability greater than or equal to . Thus some way of discriminating between universal Turing machines is called for.

-

Technically, the diachronic language “just before”/”just after” is a mistake. It fails to model cases of forgetting, or loss of discriminating power of evidence. This was shown by Arntzenius (2003). ↩