QALYs/$ are more intuitive than $/QALYs

Cross-posted to the effective altruism forum.

Summary

Cost-effectiveness estimates are often expressed in $/QALYs instead of QALYs/$. But QALYs/$ are preferable because they are more intuitive. To avoid small numbers, we can renormalise to QALYs/$10,000, or something similar.

Cost-effectiveness estimates are often expressed in $/QALYs

Four examples:

GiveWell, “Errors in DCP2 cost-effectiveness estimate for deworming”:1

Eventually, we were able to obtain the spreadsheet that was used to generate the $3.41/DALY estimate. That spreadsheet contains five separate errors that, when corrected, shift the estimated cost effectiveness of deworming from $3.41 to $326.43. We came to this conclusion a year after learning that the DCP2’s published cost-effectiveness estimate for schistosomiasis treatment – another kind of deworming – contained a crucial typo: the published figure was $3.36-$6.92 per DALY, but the correct figure is $336-$692 per DALY. (This figure appears, correctly, on page 46 of the DCP2.)

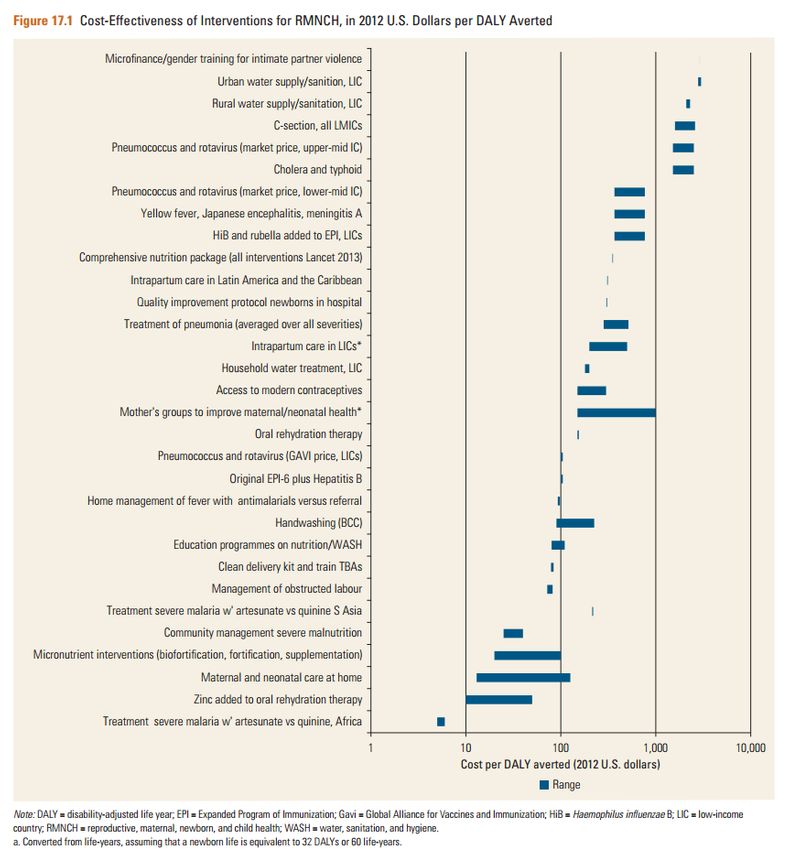

DCP3, “Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health”:

Michael Dickens, “Charities I would like to see”:

This would cost about $5 per rat per month plus an opportunity cost of maybe $500 per month for the time spent, which works out to another $5 per rat per month. Thus creating 1 rat QALYs costs $120 per year, which is $240 per human QALYs per year.

Deworming treatments cost about $30 per DALY. Thus a rat farm looks like a fairly expensive way of producing utility.

GiveWell, “Mass Distribution of Long-Lasting Insecticide-Treated Nets (LLINs)” uses cost per life saved:

LLIN distribution is one of the most cost-effective ways to save lives that we’ve seen. Our best guess estimate comes out to about $3,000 per equivalent under-5 year old life saved (or, excluding developmental impacts, $7,500 per life saved) using the total cost per net in the countries we expect AMF to work over the next few years.

QALYs/$ are preferable to $/QALYs

As long as we compare opportunities to do good by looking at the ratio of their cost-effectiveness, $/QALYs is equivalent to QALYs/$.

However, even if we know that we ought to be using ratios of cost-effectiveness, our System 1 may sometimes implicitly be using differences (subtractions) of cost-effetiveness. This can lead to problems when using $/QALYs which are entirely avoided if we use QALYs/$.

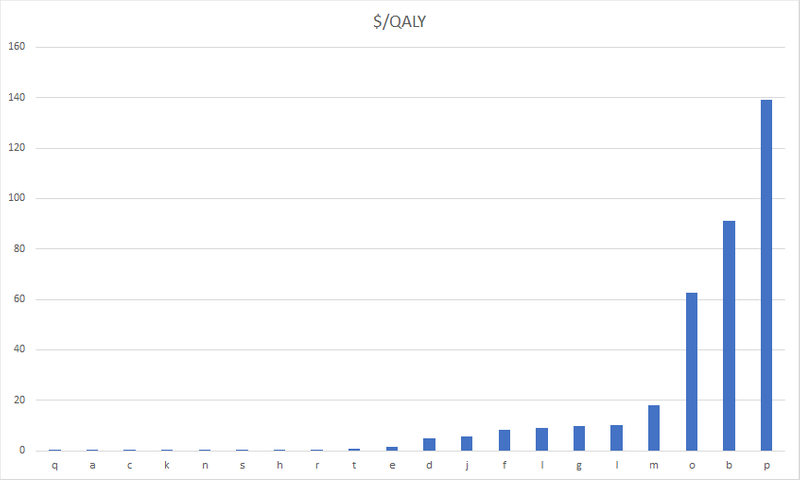

Suppose we have 20 charities - whose cost-effectiveness follows a log-normal distribution. I have plotted bar graphs of these values expressed in $/QALYs and in QALYs/$.

Looking at this graph, we are immediately attracted to the right-hand side. That’s where the big, visible differences in bar height are. So we feel that the high-hand side is where most of the action is. We may have the intuition that most of the gains are to be had by switching away from from charities like , , and , in favour of charities like , and . This is because we would implicitly be using differences instead of ratios.

In reality, of course, what’s crucial is the left-hand side of the graph. Charity produces about 9 times more value than charity , while charity is only 1.5 times better than charity .

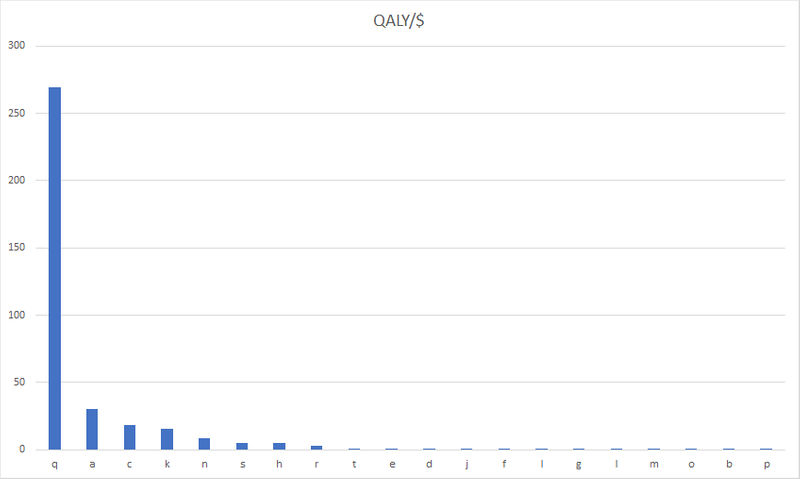

If we had used QALYs/$, this would have been easier to see. Here, the importance of picking the best charity (rather than a merely good one) stands out visually.

When we use QALYs/$, both products and subtractions give us the correct result. That is why QALYs/$ are preferable.

Small numbers

One potential problem with using QALYs/$ is that we end up with very small numbers. Small numbers can be unintuitive. It’s hard to picture 0.05 and 0.1 of something, and easy to picture 20 and 10 of something.

But this problem can easily be solved by multiplying the small numbers by a large constant. This is what we did with the Oxford Prioritisation Project, and it’s also what Toby Ord does in “The moral imperative towards cost-effectiveness”.

Further reading

By the way, this exact phenomenon is well documented in the domain of car fuel efficiency. See “The MPG Illusion”, Science Vol. 320, Issue 5883, pp. 1593-1594, DOI: 10.1126/science.1154983.

Bastian Stern also has posts explaining how $/QALYs create problems when we use arithmetic means, and when we look at proportional improvements between charities. This is not surprising, since arithmetic means and proportions are essentially based on subtraction.

Recommendation

Wherever possible, we should stop using $/QALYs and use QALYs/$10,000, or something similar.

-

Of course, there are also many examples of people correctly using QALYs/$. See for instance “The moral imperative towards cost-effectiveness”, or chapter 3 of “Doing Good Better”. ↩