Oxford Prioritisation Project Review

By Jacob Lagerros and Tom Sittler

To discuss this document, please go to the effective altruism forum.

Short summary

The Oxford Prioritisation Project was a research group between January and May 2017. The team conducted research to allocate £10,000 in the most impactful way, and published all our work on our blog. Tom Sittler was the Project’s director and Jacob Lagerros was its secretary, closely supporting Tom. This document is our (Jacob and Tom’s) in-depth review and impact evaluation of the Project. Our main conclusions are that the Project was an exciting and ambitious experiment with a new form of EA volunteer work. Although its impact fell short of our expectations in many areas, we learned an enormous amount and produced useful quantitative models.

Contents

- Short summary

- Executive summary

- The impact of the Project

- Main challenges

- Should there be more similar projects? Lessons for replication

- More general updates about epistemics, teams, and community

Executive summary

A number of paths for impact motivated this project, falling roughly into two categories: producing valuable research (both to inform and to inspire) and empowering people (by making them more knowledgeable, by improving the local community…).

We feel that the Project’s impact fell short of our expectations in many areas, especially in empowering people but also in producing research. Yet we are proud of the Project, which was an exciting and ambitious experiment with a new form of EA volunteer work. By launching into this unexplored space, we have provided significant value of information for ourselves and the EA community.

We believe that we increased the prioritisation skill of team members only to a small extent (and concentrated on one or two people), much less than we hoped. We encountered severe challenges with a heterogeneous team, and an eventual team breakdown that threatened the existence of the Project.

On the other hand, we feel confident that we learned an enormous amount through the Project, including some things we couldn’t have learned any other way. This goes from team management under strong time pressure and leadership in the face of uncertainty, to group epistemics and quantitative-model-building skills.

Research-wise, we are happy with our quantitative models, which we see as a moderately useful contribution. We are less excited about the rest of our output, which consumed a lot of time yet feels less relevant.

We’d like to thank everyone on the team for making the Project possible, as well as Owen Cotton-Barratt and Max Dalton for their valuable support.

The impact of the Project

What were the goals? How did we perform on them?

In a document I wrote in January 2017, before the project started, I identified the following goals for the project:

-

Publish online documents detailing concrete prioritisation reasoning

This has direct benefits for people who would learn from reading it, and indirect benefits by encouraging others to publish their reasoning too. Surprisingly few people in the EA community currently write blog posts explaining their donation decisions in detail. -

Produce prioritisation researchers

Outstanding participants of the Oxford Prioritisation Project may be made more likely to become future CEA, OpenPhil, or GiveWell hires. -

Training for earn-to-givers

It’s not really useful for the average member of a local group to become an expert on donation decisions. Most people should probably defer to a charity evaluator. However, for people who earn to give and donate larger sums, it’s often worth spending more time on the decision. So the Oxford Prioritisation Project could be ideal training for people who are considering earning to give in the future. -

Give local groups something to do (see also Scott Alexander on “pushing vs pulling goals”) Altruistic societies or groups may often volunteer, organise protests, write a policy paper, fundraise, etc., even if the impact on the world is actually negligible. These societies might do these things just to gives their members something to do, create a group they can feel part of, and give the society leaders status. But within the effective altruism movement, many of these low-impact activities would appear hypocritical. People in movement building have been thinking about this problem. The Centre for Effective Altruism and other organisations have full-time staff working on local group outreach, but they have not to my knowledge proposed new “things to actually do”. The Project is a thing to do that is not outreach.

-

Heighten the intellectual level of local groups

*Currently most of the EA community is intellectually passive. Many of us have a superficial understanding of prioritisation, we mostly use heuristics and arguments from authority. By having more people in the community who actually do prioritisation (e.g. who actually understand GiveWell’s spreadsheets), we increase the quality of the average conversation. *

In addition to these give object-level goals, a sixth goal:

- The value of information of the Oxford Prioritisation Project

Much of the expected impact of the Project comes from discovering whether this kind of project project can work, and whether it can be replicated in local groups around the world in order to get the object-level impacts many times over

Publish online documents detailing concrete prioritisation reasoning (1)

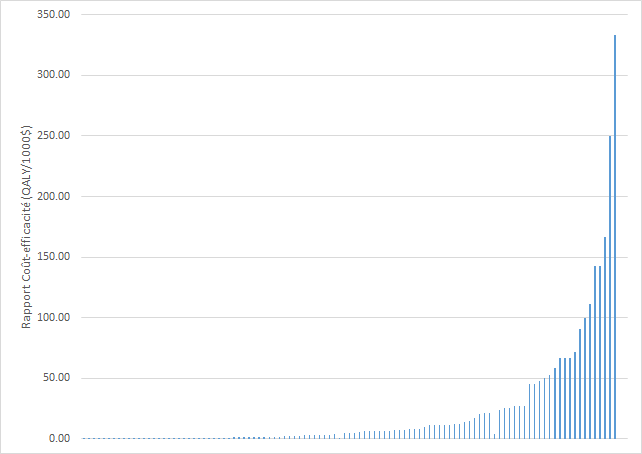

Quantity-wise, this goal was achieved. We published 38 blog posts, including individuals describing their current views, minor technical contributions to bayesian probability theory, discussion transcripts and, most importantly, quantitative models.

However, the extent to which our content engaged with substantial prioritisation questions, and was intellectually useful to the wider EA community, was far less than we expected. Overall, we feel that our substantial intellectual contribution were our quantitative models. Yet these were extremely speculative and developed in the last few weeks of the Project, while most of the preceding work was far less useful.

Regarding “direct benefits for people who would learn from reading” our research: this is very difficult to evaluate, but our tentative feeling was that this was lower than we expected. We received less direct engagement with our research on the EA forum than we expected, and we believe few people read our models. Indirectly, the models were referenced in some newsletters (for example MIRI’s). However, since our writings will remain online, there may be a small but long-lasting trickle of benefits into the future, from people coming across our models.

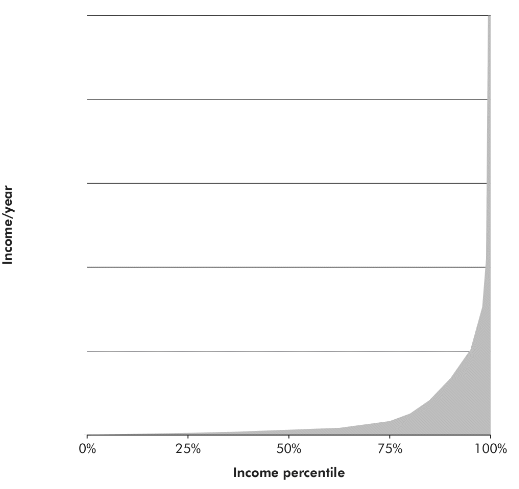

Though we did not expect to break major new conceptual ground in prioritisation research, we believed that the EA community provides too many ‘considerations’-type and too few ‘weighing’-type1 arguments. Making an actual granting decision would hopefully force us to generate ‘weighing’-type arguments, and this was a major impetus for starting the Project. So, we reasoned, even though we might not go beyond the frontier of prioritisation research, we could nonetheless be useful to people with the most advanced EA knowledge, by producing work that helps aggregate existing research into an actionable ranking. We think we were moderately successful in this respect, thanks to our quantitative models.

Prioritisation researchers (2)

This is technically too early to evaluate, but we are pessimistic about it: we do not think the project caused any member who otherwise would not have considered it to now consider prioritisation research as a career2. This is based on impressions of, and conversations with, members.

This goal was a major factor in our decisions of which applicants to admit to the project. We selected several people who had less experience with EA topics, but who were interested and talented, in order to increase our chance of achieving this sub-goal. In retrospect, this was clearly a mistake, since getting these people up to speed proved far more difficult than we expected, and we still don’t think we had a counterfactual impact on their careers. Looking back, we recognise that there was some evidence for this that we interpreted incorrectly at the time, so we made a mistake in expectation, but not an obvious one.

As often, we suspect the impact in this category was extremely skewed across individuals. While we think we had no impact on most members, we think there is a small (<5%)3 chance that we have counterfactually changed the interests and abilities of one team member, such that this person will in the future work in global priorities research.

Training for earn-to-givers (3)

This was not achieved, for two reasons. While at the outset, we believed that there were about 3 team members who might consider earning to give in the future, by the end we think only one of them has a >50% chance of choosing that career path. So even though we provided an opportunity to practice prioritisation thinking, and especially quantitative modelling, we don’t think we had an impact by improving the decisions of future earn-to-givers. Regardless, we believe that this practice failed to increase the prioritisation skill of our team (see previous sections), so we wouldn’t have had impact here anyway.

Give local groups something to do (4)

This goal was achieved. We designed and implemented a new form of object-level group engagement that could theoretically be replicated in other locations. However, it’s debatable whether the cost:benefit ratio of such replications is sufficiently high. See the section: “Should there be more similar projects? Lessons for replication”

Local group epistemics (5)

This goal was not achieved.

One impulse for starting the project was a frustration about the lack of in-depth, object-level intellectual activity in the local student EA community, which we (Jacob and Tom) are both part of. Current activities look like:

- Attending and organising introductory events

- Social events, where conversations focus on:

- Discussing new developments in EA organisations

- Philosophy, especially ethics

- ‘Considerations’-type arguments, with a special focus on controversial, or extreme arguments. Much repetition of well-known arguments.

- Fundraising

We wanted to see more of:

- Discussion of ‘weighing’-type arguments, with a focus on specific, quantifiable claims

- Instead of repetition of known considerations, discussion of individual people’s actual beliefs on core EA questions, and what would change their minds. Conversations at the frontier of people’s knowledge.

- Knowing when people change their minds

- Individuals conducting shallow (3-20 hour), empirical or theoretical research projects, and publishing them online

We did not believe that the Project alone could have achieved any of these changes. But we were optimistic that it would help push in that direction. We thought members of the local group would become excited about the Project, discuss its technical details, and give feedback. We also thought that team members would socialise with local group members and discuss their work, and hoped that the Project would serve as a model inspiring other more intellectually focused activities. None of these happened.

The local community was largely indifferent to the Project, as evidenced by an attendance of no more than 10 people at our final decision announcement. Throughout the Project, there was little interaction between the community and team members. In retrospect, we think we could have done more to facilitate and encourage such interaction. But we were already very busy as things were, so this would have needed to trade off against another of our activities.

Overall we clearly didn’t achieve this goal.

The value of information of the Oxford Prioritisation Project (6)

This goal was arguably achieved, in the sense that the Project produced several unexpected results which carry important implications for future projects. The information gained included:

- Directly applicable knowledge about how to run similar Projects. See below, “Should there be more similar projects? Lessons for replication”

- Knowledge of a more general relevance, about how to achieve good results when a group of people are facing an intellectual challenge for which no set guidelines exist. See below, “More general updates about epistemics, teams, and community.”

Learning value for Jacob and Tom

The Project was a huge learning experience for us both, and especially strongly for Tom. This was the first time Tom led a team. Running a group of prioritisation researchers was a very different task from academic projects or internships we had been involved with in the past.

Our guess is that between 25% and 75% of the value created by the Project was through our becoming wiser and more experienced. This admittedly subjective conclusion relies on a number of difficult-to-verbalise intuitions, to the effect that we came out of the project knowing more about our own strengths and weaknesses, and how people and groups work. Since we both plan to give a substantial weight to altruistic considerations in our career decisions, this could be impactful.

Throughout the Project, Tom kept a journal of specific learning points, mostly for his own benefit but also for others who would potentially be interested in replicating the Project. He originally planned to turn these notes into a well-structured and detailed retrospective, but completing this work now looks as though it would not be worth the time cost. Instead he is publishing his notes with minimal editing here. These files reflect Tom’s views at the time of writing (indicated on each document); he may not endorse them in full anymore. They cover the following topics, in alphabetical order:

- Anchoring vs Leading by example

- Dealing with public criticism

- Emotions when leading

- Framing: global prioritisation vs. expertise-building research

- Goals of the Oxford Prioritisation Project

- How can we encourage people to read each other’s work?

- Iterative vs exploratory approaches

- Leadership

- Obvious mistakes and “grokking” it

- People are good at just not dropping out

- Providing tightly structured templates for team members to write in

- Running good meetings

- Teaching basic arguments and concepts

- Team selection

- Team vs work group

- The epistemic atmosphere of the Oxford Prioritisation Project

- Timeline of events

- Value of information

- Website

- Why did version 0 fail to motivate people?

What were the costs of the project?

Student time

Tom tracked 308 focused pomodoros (~ 150 hours) on this project, and estimates that the true number of focused hours was closer to 500. Tom also estimates he dedicated at least another 200 hours of less focused time to the Project.

Jacob estimates he spent 100 hours on the Project.

CEA money and time

We would guess that the real costs of the £10,000 grant were low. At the outset, the probability was quite high that the money would eventually be granted to a high-impact organisation, with a cost-effectiveness not several times smaller than CEA’s counterfactual use of the money4. In fact, the grant was given to 80,000 Hours.

The costs of snacks and drinks for our meetings, and logistics for the final event were about £500, covered by CEA’s local group budget.

We very tentatively estimate that Owen Cotton-Barratt spent less than 5 hours, and Max Dalton about 15 hours, helping us with the Project over the six months in which it ran. We are very grateful to both for their valuable support.

Main challenges

We faced a number of challenges; we’ll describe only the biggest ones, taking them in rough chronological order.

Different levels of previous experience

Heterogenous starting points

Some team members were experienced with advanced EA topics, while others were beginners with an interest in cost-effective charity. This was in part because we explicitly aimed to include some less experienced team members at the recruitment stage (see above, “2: Prioritisation researchers”). But an equally important factor was that, before we met them in person, we overestimated some team members’ understanding of prioritisation research.

We selected the team exclusively with an online application form. Once the project started, and we began talking to them in person, it quickly became clear that we had overestimated many team members’ familiarity with the basic arguments, concepts, and stylised facts that constitute the groundwork of prioritisation work. Possible explanations for our mistake include:

- Typical mind fallacy, or insufficient empathy with applicants. Because we knew much more, we unconsciously filled gaps in people’s applications. For example, if someone was vaguely gesturing at a concept, we would immediately understand not only the argument they were thinking of, but also many variations and nuances of this argument. This could turn into believing that the applicant had made the nuanced argument.

- Wishful thinking. We were excited by the idea of building a knowledgeable team, so we may have been motivated to ignore countervailing evidence.

- Underestimating applicant’s desire and ability to show themselves in the best light. We neglected to account for the fact that applicants could carefully craft their text to emphasise their strengths, and mistakenly treated their applications more as if they were transcripts of an informal conversation.

- Insufficiently discriminative application questions. Tom put significant effort into designing a short but informative application. Applicants were asked to provide a CV, a Fermi estimate of the total length of waterslides in the US, and a particular research question they expected to encounter during the project, along with their approach for answering it. After the fact, we not only think that these specific questions were suboptimal5, but also see clear ways the application process as a whole could have been done very differently and much better (see section “Smaller team” below). We struggle to think of evidence for this that we interpreted incorrectly at the time, so this may still have been the correct decision in expectation.

Continued heterogeneity

A heterogenous team alone would not have been a major problem if we hadn’t also dramatically overestimated our ability to bring the less experienced members up to speed.

We had planned to spend several weeks at the beginning of the project working especially proactively with these team members to fill remaining gaps in their knowledge. We prepared a list of “prioritisation research concepts” and held a rotating series of short presentations on them and we gave specific team members relevant reading material. We expected that team members would learn quickly from each other and “learn by doing”, from trying their hand at prioritisation.

In fact, we made barely any progress. For all except one team member, we feel that we failed to bring them substantially closer to being able to meaningfully contribute to prioritisation research: everyone remained largely at their previous levels, some high, some low6.

This makes us substantially more pessimistic about the possibility of fostering EA research talent through proactive schemes rather than letting individuals learn organically. (EA Berkeley seemed more positive about their student-led EA class, calling it “very successful”, but we believe it was many times less ambitious). We feel more confident that there is a basic global prioritisation mindset, which is extremely rare and difficult to change by certain kinds of outside intervention, but essential for EA researchers.

Team breakdown

We were struggling to create a cohesive team where everyone was able to contribute to the shared goal of optimally allocating the £10,000, and was motivated to do so. Meanwhile, some team members became less engaged, perhaps as a result of the lack of visible signs of progress. Meeting attendance began to decline, and the problem worsened until the end of the Project, at which point four out of nine team members had dropped out. After the project only 3 out of 7 team members took the post-project survey. The results have informed our estimates throughout this evaluation.

While understanding that the dropout rate for volunteer projects is typically high, we still perceived this as a frustrating failure. An unexpected number of team members encountered health or family problems, while others simply lost motivation. Starting around halfway through the Project, the majority our efforts were focused on averting a complete dissolution of the team, which would have ended the Project.

As a result, we decided to severely curtail the ambition of the Project by choosing our four shortlisted charities ourselves, without team input, and according to different criteria than those we had originally envisioned7. We had been planning to shortlist the organisations with the highest expected impact, as a team, in a principled way. Instead we (Jacob and Tom) took into account our hunches about expected impact as well as the intellectual value of producing a quantitative model of a particular organisation, in order to arrive at a highly subjective and under-justified judgement call.

We are satisfied with this decision; we believe that it allowed us to create most of the value that could still be captured at that stage, given the circumstances. With a smaller team and a more focused goal, we produced the four quantitative models which led to our final decision.

Should there be more similar projects? Lessons for replication

Did the Project achieve positive impact?

Costs and benefits

See above, “What were the costs of the project?”.

Tom’s feelings

It’s important to make a distinction between the impacts of the Project from a purely impartial perspective, and the impacts according to my values, which give a much larger place to me and my friends’ well-being.

Given that the object-level impacts (see above, “The impact of the Project”) were, in my view, low, effects on Jacob’s and my personal trajectories (our academic performance, well-being, skill-building) could be important, even from an impartial point of view.

Against a counterfactual of “no Oxford Prioritisation Project” (say, if the idea had not been suggested to me, or if we had not received funding), I would guess with low confidence that the Project had negative (impartial) impact. Without the Project, I would have spent these 6+ months happier and less stressed, with more time to spend on my studies. I plan to give significant weight to altruistic considerations in my career decisions, so this alone could have made the project net-negative. In addition, I believe I would have spent significant time thinking about object-level prioritisation questions on my own, and published my thoughts in some form. On the other hand, I learned a lot about team management and my own strengths and weaknesses through the Project. All things considered, I suspect that the Project was a little bit less good than this counterfactual.

When it comes to my own values, I’m slightly more confident that the Project was negative against this counterfactual. If offered to go back in time to re-experience the same events, I would probably decline.

Both impartially and personally speaking, there are some nearby counterfactuals against which I am slightly more confident that the Project was negative. These mostly take the form of developing quantitative models with two or three close friends, in an informal setting, and iterating on them rapidly, with or without money to grant. However, these counterfactuals are unlikely; at the time I didn’t have the information to realise how good they would be.

Going back now to the impartial perspective: despite my weakly held view described above, there are several scenarios for positive impact from the Project which I find quite plausible. For example, I would consider the Project to have paid for itself relative to reasonable counterfactuals if:

- what I learned from the Project helps me improve a major career decision

- the team member mentioned above ends up pursuing global priorities research

- we inspire another group to launch a project inspired by our model, and they achieve radically better outcomes

Things we would advise changing if the project were replicated

Less ambition

Global prioritisation is very challenging for two reasons. First, the search space contains a large number of possible interventions and organisations. Second, the search space spans multiple very different focus areas, such as global health and existential risk reduction.

The Project aimed to tackle both of these challenges. This high level of ambition was a conscious decision; we were excited by the lack of artificial restrictions on the search space. Though we had no unrealistic hopes of finding the truly best intervention, or of breaking significant new ground in prioritisation research, we still felt that an unrestricted search space would make the task more valuable, it made it feel more real, and less like a student’s exercise. We implicitly predicted that other team members would also be more motivated by the ambitious nature of the Project, but this turned out not to be the case. If anything, motivation increased after we shifted to less ambitious goals.

Given that our initial goal proved too difficult, even given the talent pool available in Oxford, we would recommend that potential replications restrict the search space to eliminate one of the two challenges. This gives two options:

- Prioritisation among a pre-established shortlist of organisations working in different focus areas. (This is the option we chose towards the end of the Project).

- Prioritisation in a (small) focus area, such as mental health or biosecurity.

We would weakly recommend the former rather than the latter, because we already tried it with moderate success, and because it allows starting immediately with quantitative models of the shortlisted organisations (see below, “Focus on quantitative models from the beginning”).

Shorter duration

Given the circumstances, we believe the Project was too long. A shorter project means less is lost if the Project fails, and the closer deadline could be motivating.

We would recommend one of two models:

- 1-month project with meetings and work sessions at intervals

- 1 week retreat, working on the project full-time

Our most important work, building the actual quantitative models and deciding on their inputs, was done in about this amount of time. The large, early part of the project centering around learning and searching for candidate organizations, was marginally not very useful (see e.g. section “Continued heterogeneity” above).

Use a smaller grant if it seems easier

We initially believed that the relatively large size of the grant (£10,000) would motivate team members not only to work hard, but, more importantly, to be epistemically virtuous – that is, to focus their efforts on actions to improve the final allocation rather than ones that felt fun or socially normative. We now believe that this effect is small, and does not depend much on the size of the grant. For more information, see section “More general updates about epistemics, teams and community”.

Where the £10,000 figure may have helped is through getting us more and better applicants by signalling serious intent. But we are very uncertain about this consideration and would give it low weight.

Overall, our view is that the benefits of a larger grant size are quite small, relative to other strategic decisions, and that a £1000-2000 grant might have achieved nearly all the same benefits8. On the other hand, the true monetary cost of the grant is low (see above, “CEA money and time”). Therefore our tentative recommendation is: a £10,000 grant may still be worth getting, but don’t worry too much about it. Be upfront to the funder about the small effect of the money, and consider going ahead anyway if they give you less.

Focus on quantitative models from the beginning

One of the surprising updates from the Project was that we made much more progress, including the less experienced team members, once we began working on explicit quantitative models of specific organisations. (See section “More general updates about epistemics, teams and community”.) So we would recommend starting with quantitative models from the first day, even when they are very simple. This may sound surprising, but we urge you to try it9.

More homogenous team

We severely overestimated the degree to which we could bring less experienced members of a heterogeneous team up to speed (see above, “Different levels of previous experience”). So we would recommend a homogenous team, with all members meeting a high threshold of experience.

Smaller team

We started with a model where, very roughly, people are either good, conscientious team members, or they get de-motivated and drop out of the team. Under this model, dropouts are not very costly. You lose a team member, but you also lose overhead in dealing with them. So that is a reason to have a bigger team to start with. However, what we actually observed is that demotivated people don’t like working, but the one thing they dislike more is dropping out. Without speculating about the underlying reasons, a common strategy while demotivated (that we ourselves have also been guilty of in the past) is to do the minimal amount of work required to avoid dropping out. Hence, future projects should start with a small team of fully dedicated members rather than a larger team hoping to provide some “buffer” should a team member drop out.

Having a smaller team also means expending more effort selecting team members; doing so should also help with the problem raised in the above subsection. Although it seemed to us that we had already put a lot of resources into finding the right team, we now see that much more could have been done here, for example:

- a fully-fledged trial period; consisting of a big, top-down managed team from which the most promising few members are then selected to go on (although we worry this could introduce negative anti-cooperative norms and an unpleasant atmosphere).

- making the application process the following: candidates build a quantitative model, receive feedback, and go back to submit a second version; they are then evaluated on the quality of their models

More general updates about epistemics, teams, and community

We had several hypotheses about how a project like this would affect the members involved, as well as the larger effective altruism community in which it took place. Here are some of our updates. Of course, the Project is only a single data point. Nonetheless, we think it still carries evidence in the same sense that, say, an elaborate field-study might be important without being an RCT.

The epistemic atmosphere of a group will be more truth-seeking when a large donation is conditional on its performance.

Update: substantially lower credence

There are at least two reasons why human intellectual interaction is often not truth-seeking. First, there are conflicting incentives. These can take the form of both internal, cognitive biases or external, structural incentives.

To some extent the money helped realign incentives. The looming £10,000 decision provided a Schelling point that could be used to end less useful discussions or sub-projects without the violation of social norms that this often entails otherwise.

Nonetheless, the atmosphere also suffered from many common cognitive biases. These includes things like deferring too much to perceived authorities, and discussing topics that one likes, feels comfortable with or know many interesting facts about. It is possible that the kind of disciplining “skin in the game” effect we were hoping for failed to occur since the grant was altruistic, and of little relevance to team members personally. In response to this, team members also pledged a secret amount of their own money to the eventual recipient (with pledges ranging from £0 to £200)10. It is difficult to disentangle the consequences of this personal decision from the donation at large, but it might still have suffered the same altruistic problem. Given how insensitive people are to astronomical differences in charity impact in general, the choice of which top charity one’s donations go to might not make a sufficient psychological difference to offset other incentives.

Second, truth-seeking interaction is partly difficult not because of misaligned incentives, but because it requires certain mental skills that have to be deliberately trained (see also “Different levels of previous experience”). Finding the truth, in general, is hard. For example, we strongly encouraged team members to center discussions around cruxes, but most often the cruxes members gave were not actually things that would change their minds about X, as opposed to generic evidence regarding X or evidence that would clearly falsify X but that they strongly never expected to be found. This was true for basically all members of the Project, often including ourselves.

Instead of the looming, large donation, the epistemic atmosphere seems to have been positively impacted by things like guiding disagreements in relation to which quantitative model input they would change, and working within a strict time limit (e.g. a set meeting ending). For more on this, see the section “Focus on quantitative models from the beginning”.

A major risk to the project is people hold on too strongly to their pre-Project views

Update: lower credence

We nicknamed this the “pet charities” problem: participants start the project with some views about which grantees are most cost-effective, and see themselves as having to defend that view. They engage with contrary evidence, but only to argue against it, or to find some reason their original grantee is still superior.

This was hardly a problem, but something in the vicinity was. While people didn’t strongly defend a view, this was mostly because they didn’t feel comfortable engaging with competing views at all. Instead, participants strongly preferred to continue researching the area they already knew and cared most about, even as other participants were doing the same thing with a different area. Participants’ different choice of area implied disagreeing premises, but they proved extremely reluctant to attempt to resolve this disagreement. We might call this the “pet areas” problem or the problem of “lower bound propagation”. (Because participants may informally be using the heuristic: “consider only interventions better than X”, with very different Xs).

Another problem that proved bigger than pet charities was over-updating on authority opinion (such as Tom’s current ranking of grantees). We see this as linked with the lack of comfort or confidence mentioned above.

A large majority of team applicants would be people we know personally.

Update: false

We’re both socially close to the EA community in Oxford. We expected to more or less know all applicants personally: if someone was interested enough in EA to apply, we would have come across them somehow.

Instead, a large number of applications were from people we didn’t know at all, a few of which ended up being selected for the team. We update that, at least in Oxford, there are many “lurkers”: people who are interested in EA, but find the current offerings of the local group uninspiring, so that they don’t get involved at all. There appear to be many talented people who are only prepared to work on an EA project if it stands out to them as particularly interesting. Although we generally would advise caution, this could be one reason to be more optimistic about replications of the Project.

-

A useful distinction is between ‘considerations’-type arguments and ‘weighing’-type arguments. Considerations-type arguments contain new facts or reasoning that should shift our views, other things being equal, in a certain direction. Sometimes, in addition to the direction of the shift, these arguments give an intuitive idea of its magnitude. Weighing-type arguments, on the other hand, take existing considerations and use them to arrive at an all-things-considered view. The magnitude of different effects is explicitly weighed. Considerations-type arguments involve fewer questionable judgement calls and more conceptual novelty, which is one reason we believe they are oversupplied relative to weighing-type arguments. While Tom believed this sufficiently strongly to contribute to motivating him to launch the Project, we both agree that this is something reasonable people can disagree about. On a draft of this piece, Max Dalton wrote: “They also tend to produce shifts in view that are less significant, both in the sense of less revolutionary, and in the sense of the changes tending to have less impact. This is partly because weighing-type arguments are more commonly used in cases where you’re picking between two good options. Because I think weighing-type arguments tend to be lower-impact, I’m not sure I agree with your conclusion. My view here is pretty low-resilience.” ↩

-

To be clear, however, there are team members who are seriously considering that career path. ↩

-

Tom’s guess: 15% chance this person goes into prioritisation research. Conditional on him or her doing so, a ~30% chance we caused it. ↩

-

We also had a safeguard in place to avoid the money being granted to an obviously poor organisation, in case the project went dangerously off the rails: Owen Cotton-Barratt had veto power on the final grant (although he says he would have been reluctant to use it). ↩

-

The Fermi question was too easy in that it didn’t help discriminate between top applicants, and that the research proposal question was too vague and should have required more specifics. ↩

-

Jacob adds: “It should be emphasized that we are disregarding any general intellectual progress here. It is plausible that several team members learned new concepts and practiced critical thinking, and as a result grew intellectually from the project – just not in a direction and extent that would help with global prioritisation work in particular.” ↩

-

More goal flexibility, earlier on, would have been good. We had ambitious goals for the Project, which we described publicly online, and in conversations with funders and others we respect. In attempting to achieve these goals, we believe we were quite flexible and creative, trying many different approaches. But we were too rigid about the (ultimately instrumental) Project goals. Partly, we felt that changing them would be an embarrassment; we avoided doing so because it would have been painful in the short run. But it seems clear now that we could have better achieved our terminal goals by modifying the Project’s goals. ↩

-

There is significant disagreement about this among people we’ve discussed it with, on and off the team. We note that being more heavily involved in the Project seems to correlate with believing that a low grant would have achieved most of the benefits. Outsiders tend to believe that more money is good, while we who led the Project believe the effects are small. (A middle ground of £5000 has tended to produce some more agreement.) People we respect disagree with us, which you should take into account when forming your own view. ↩

-

Jacob adds: “One of our most productive and insightful sessions was when we spent about six hours deciding the final inputs into the models. It is plausible that this single session was equally intellectually productive and decision-guiding as the first few weeks of the project combined.” ↩

-

A team member comments that “skin in the game”-effects may encourage avoiding bad outcomes more than working extra hard for good outcomes: “Subjectively, I felt it as a constant ‘safety net’ to know that we’d most likely give to a good charity that ends up being in a certain range of uncertainty that the experts concede, and that it was almost impossible for us to blow 10,000GBP on something that would be anywhere near low impact”. ↩